――“Never Look Away” is such a beautiful and epic film. Why did you want to tell this particular story?

Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck: I’ve been looking for many years to find a story about how a person overcomes suffering and used that suffering to create art. Originally, I wanted to make it about an opera composer who turns all the terrible things that happened in his life into art. He’s poor and sick and the woman he loves doesn’t love him that he goes into his depressing little apartment and turns it all into beautiful arias. We find his life on the big stage at the end of the movie in this beautiful form. I thought that would be an interesting cinematic experiment, but I didn’t find any opera story that really was compelling enough or personal enough to tell.

――I understand that it’s not a biopic, but how did you come across Gerhard Richter’s story? What about his life that you were most inspired by?

Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck: Through a journalist with whom I had an interview actually, he told me that he’d just written a biography of Richter. I said, “Why would you do that? So much has been written about Richter. What’s the new angle?” and he said, “Well, there is this painting he did of his aunt holding him as a little baby, and she was murdered by the Nazis.” I said, “Yeah, I know that.” It’s a well-known story in Germany. He said what he found out through his research was that the father of the girl Richter ended up marrying was the guy responsible for the euthanasia program in Dresden. And I thought, OK, that’s interesting. That’s an interesting starting point for a story, because you have the victims and the criminals living together under one roof in one family. I thought that could be an interesting way maybe to tell my story of the opera composer, only now with a painter. Then I invented a whole story about what this could be like and read the book from this journalist. It was a very good book, well-researched, but it didn’t have all the exciting things that I hoped would be in it. So I said, “Well, luckily I’m not a documentary filmmaker and I don’t have to make this a biography. I’d just be inspired by one thing from his life to tell my story of the opera composer,” and then wrote this script. That’s how it all happened.

――I heard that you actually consulted with Gerhard Richter for this film. For someone like Richter who has gone through a lot in his life, I imagine that it may not be easy to talk about his past. How open was he when you talked to him?

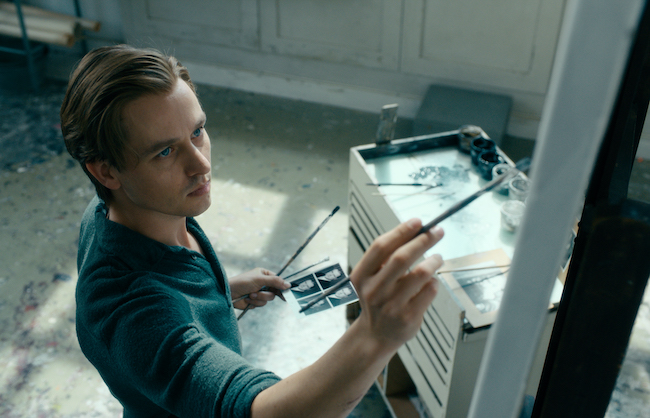

Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck: I think I just caught him at the right moment. He was in a little bit of a painter’s block which then resolved after he talked through all these things. I think in a way, he was probably using me as much as I was using him [laughs.] Because I was a free analyst and he was a free interview subject and researcher to me. So we went through his whole life and went to Dresden together for a few days. We visited his childhood home where he hadn’t been since then, where he lived with his wife in the house of the Nazi doctor. Then we went to where his old studio was, where he did his first paintings. We went to all those places and after that, I had to go to Munich for a few days before I returned to Cologne where he lives. While I was in Munich, in maybe three days, he had painted 20 really, really good paintings, because he’d overcome his painter’s block by thinking through his life in a structured way. So I think I was just lucky that I got him at the right moment.

――I like how the movie talks about that art can’t change the world, but it can comfort you. What were some of the things that he told you that gave you inspirations?

Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck: What I find just impressive about him is that for all the complicated sides that he may have as a human being, as an artist, he is incredibly honest and always in search of the truth. That’s something that I tried to bring into this character. It doesn’t matter, you can lie about your life, you can be a terrible husband, you can be anything, but if you are honest in your art, you are still a great artist, you know?

――In the movie, Kurt’s aunt tells him, “Never look away, everything true is beautiful,” and he keeps that advice close to his heart for the rest of his life. Do you have any words or advice that you keep close to your heart?

Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck: I tried to put everything that I know about art into the movie, so I don’t know much more than that [laughs.] “Everything true is beautiful” is a daring statement the aunt makes. Because what does that mean? Does that mean that some unspeakable tragedy and atrocities of a war are beautiful? In a way, what I did is I tried to stage everything in this film as beautifully and as humanly possible. I tried to make the most beautiful film ever made. That was kind of my ambition while showing the worst atrocities that were ever committed, in a way, to put this thesis of the aunt to an extreme test. Is that really true? Probably not, but I want to stretch it as far as you could.

――I see.

Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck: The one thing that I kind of remind myself of in art, in storytelling and in anything is that it’s too easy to look at life in a dark way. I think if that’s all you can do, I don’t think that you are really called to be an artist. Because as you were saying, I go to art for some kind of comfort, for some kind of consolation about problems, and for ways to solve problems. It’s easy to look at life as something depressing and dark and just say, “Look, we will die by the end of our lives and all of the people that we love, we will see them die if we don’t die first.” That’s a bleak way of looking at life. It may be true, but I think it’s not a very artistic way of looking at life. I think an artistic way of looking at life is trying to see why it is still worthwhile.

――In the film, Kurt is always searching for the truth. It is his personal truth that he’s searching for, yet there is so much we could learn today through his eyes. 2020 has been a crazy year that none of us had imagined maybe a year ago, but what is the truth for you in this world today?

Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck: It has to be up to every individual to find that truth within herself or himself. The thing I despise the most is group think and conformism because it’s in a way giving up on yourself as an individual. I so much believe in the individual. I do think that on the very fundamental level, if we manage to go there, we find there are incredible commonalities and incredible similarities between people. But if there has been an advantage to this crisis, it’s that people have been forced to live without many of the distractions, certainly of the distractions of social life. They have been forced to look a little bit more within. So in some way, I hope that this film could be even more relevant now in COVID times because it shows how one person, by looking within for the first time, manages to really find himself and the truth of the outside world.

――We got these new creative restrictions amid the pandemic as well. As a filmmaker/creator, what do you think about your creation post-COVID?

Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck: I can see the industry opening up again even if it’s not happening in the U.S. It’s happening elsewhere. Will it still be a great theatrical experience? That of course is a question. But you know, theater was dying anyway. But scripted storytelling with actors directed by directors with a vision of what they want, that is more alive than ever before. It might take different avenues, but I think people need stories more than ever before to make sense of all the changes that are happening in the world.

――What was the biggest thing you got through making this film?

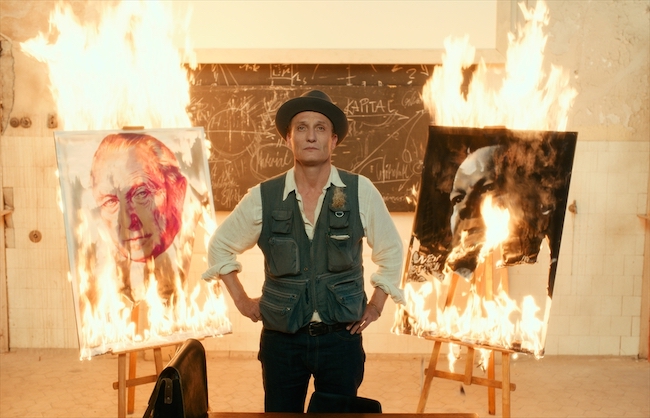

Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck: I got white hair [laughs.] It was an unbelievably difficult film to make, I hope it will never again be this hard because every little thing was an unbelievable challenge. From recreating the Degenerate art exhibit that the Nazis had where we had to employ entire armies of art forgers and artists to create these pictures, many of which were destroyed after the Nazis show these pictures, right through to just showing the distraction of Germany and making it feel real. We also felt the real responsibility towards the generation of our parents and grandparents whose lives we are telling in a way. I think all of us who worked on this film felt an incredible responsibility to do justice to their sufferings. At the same time, we got incredible reactions more than I’ve ever had for a movie, but we also got attacked more than ever as imaginable.

――What’s next for you?

Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck: I have few projects. I bought the right to this wonderful novel by a young novelist from Maine called “Everything Matters.” It’s a story of a boy who for reasons knows exactly when the world is going to come to an end. It’s about how he lives with this knowledge that he knows no one would ever believe him, but he knows it and it’s about how he lives his life. It’s a really wonderful and interesting book and I have an idea on how to turn that into what I think would be an interesting film. So that might be the next one, but we’ll see. I haven’t actually written it down yet. I’ve started and maybe that will be the next one.

text Nao Machida