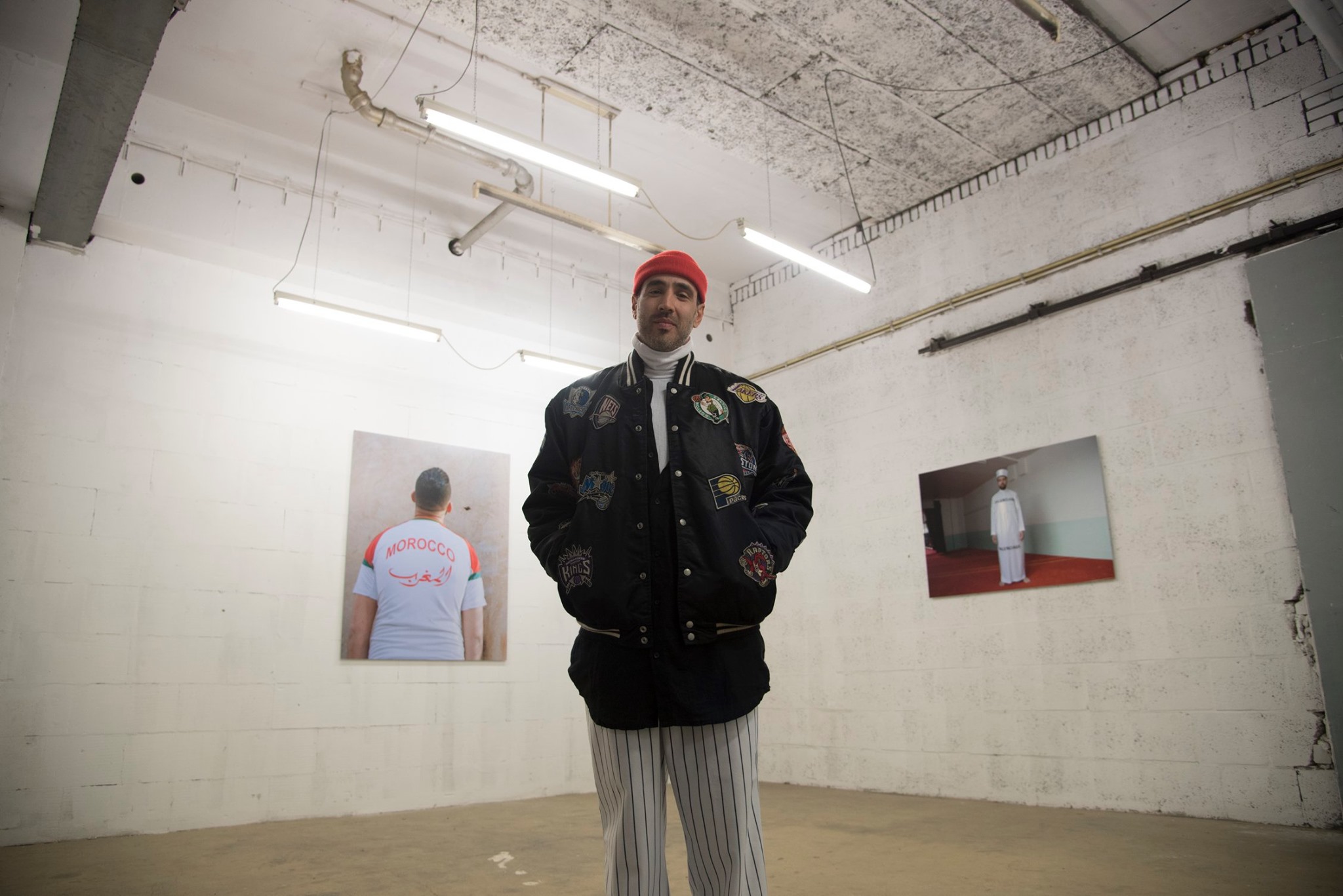

Photo by Koen Bouman

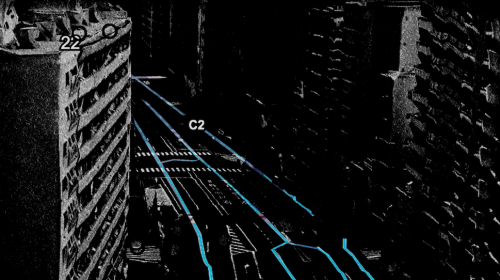

It’s comforting to think that the West is at the forefront of art and technology. An idea that artistic director of MONO, Shirin Mirachor reconsidered when she took a trip to Dubai, realizing the ravishing possibilities that the city held within it’s arts and culture scene. Thus New Radicalism was born; a four day festival that introduced new artists from the Middle East and North Africa in the field of digital arts to the Netherlands. Having an iraqi-kurdish background herself and having worked in the cultural sector for over ten years, she creates a space for the in-between; a place catered to the ones who never complied to one category or community, the foundation (A)WAKE is the big katalysator behind all this and MONO is a melting pot where people from different cultures and ethnicities come together to drink, dance and live life.

–New Radicalism was a four-day festival introducing new artists from the Middle East and North Africa in the field of digital arts. How did this idea come about ?

Shirin: We actually started a project five years ago called HIPSTER/MUSLIM which was about stereotypes and prejudice around being a Muslim. The common ground was the beard that hipsters and muslims have in common. So we tried to open up the discussion about this fear of others by presenting a hipster and a muslim next to each other. They swapped clothes and you see pictures of them before and after which makes it hard to distinguish whose who. It was a very playful project and through that I realized the need for something new for the muslim community because when they are in the news, they are usually associated with something negative. I came across this power structure between East and West and at some point, I was diving into Instagram because we had an exhibition in Dubai for this project and I was curious about what the creative scene in Dubai looked like. I was super surprised by it. I saw so many collectives and artists that I wasn’t aware of and it looked so fresh and progressive. While I was diving into it, I noticed that I got a bit insecure about it as well because I had no clue as to what was going on in the Middle East and North Africa. Because of this, I thought more about radicalism and how it is always connected to something negative and a lot of it is religious. But for me, radicalism is more about thinking outside of the box. That plus, the Middle East and North Africa within digital culture, you can see that they feel more comfortable to present their ideas now, as you don’t need these financial means to do something and there aren’t many restrictive borders. During the road I met my partner in crime Narges Mohammadi who helped me articulate all these insights into a solid framework and this was the moment that both a deep friendship as well as the festival, New Radicalism was born.

-The Festival was held over four days, can you tell us some highlights from the events that were hosted?

Shirin: It was when like minded spirits met each other in one place. I am not really poetic usually but truly that magic did happen. I always felt a little lonely and in-between; between academic and practice, intellectual field and more urban culture. Always felt that I needed to choose one. But we combined club nights with exhibitions and cultural programs into one. So it was already interesting to have a debate or talk that it is very much easy to get in touch with the speaker and maybe meet that person at night in the club. One thing we mentioned in an abstract way was the fact that we wanted to find new role models for the people who were from North Africa here. It was so special because people who normally would feel already a little excluded as ‘the other’ because he has moroccan roots, would come into a space where all of the cultural references are from the East and now he knows all of the songs that are playing. A girl came up to me a week and a half later and she told me that she needed to cry all Sunday because she was so touched. For the first time she felt proud to be Moroccan. Now we are even more motivated to keep on continuing.

-How did you find the artists for the festival? Were they already friends of yours?

Shirin: It started with talking to some friends. At first I was really vague and naive like ‘What’s up, I’m looking for Arab artists.’ And they were like ‘What the fuck is Arab artists?’ It would be the same as looking for pure Asian artists, I guess. It really didn’t make any sense so we had a discussion about what is Arab because there are so many ideas about what the Middle East actually is. We then realized it was ridiculous to just work with one curator for the whole region and we couldn’t find a curator for the job because no one actually knows as to what is happening in all of these places. In the beginning, we thought about choosing four nations and selecting the best artists from each. But because of this discussion, we thought that it was wrong to think in borders again so it was actually up to the four different curators to choose the artists. When we talked about Israel for example, we had debates on whether we should or should not include it. Both choices would be politically very sensitive so we decided it was best to let the curators decide on what they thought was best and leave it to them. It was also better for the music and educational programs. I think our role should be more humble instead of making it about ourselves. We are not capable of knowing what will work and what won’t. One thing we do reflect upon is that we know what works in the Netherlands. Especially for the content program because I was more closely involved in this area. I know Rotterdam is a working class city so I didn’t know if an educational lecture would be the best. Also finding a balance in that sense.

-The festival took place in the Zoho area, one of the last ungentrified areas near central Rotterdam, where MONO is also situated. Why was it important to situate the festival as well as the club here?

Shirin: A lot because this neighborhood is known for having minor roots. I think it is important to bring the art to the audience and not the other way around. That is why we also set up this educational program where kids from the neighborhood ages 18-25 could be one of the privileged for once and get free access to everything and one on one feedback sessions that felt quite intense. There was one time they had to make an app through augmented reality:during the educational program led by youth organization Cult North and artist Boris Battat, they made an augmented reality app that (critically) reflected on the exhibition itself. This was a very beautiful manner to create this equal give-and-take relationship between us and the students. For me, the ideal situation would be when someone who is educated would come into MONO and doesn’t really feel that comfortable because obviously it is so different to a white cube. While this kid from the neighborhood is super relaxed and talking to the curator and asking all these questions. That would be perfect.

-You have experience working in the cultural sector for over ten years. How has previous experiences helped you in the conceptualization of MONO?

Shirin: I have a background in art and economics but it was also art management. I was always interested in youth culture and counterculture and very much focused on club nights. I graduated with the thesis happiness and club nights: that combines theory of happiness within the context of a club night because there is something mysterious about the nightlife in that there are so many movements and countercultures establish themselves within clubs and in the night. But it was more about connecting brands to all of these scenes. Then at some point I had the opportunity to work at Vice London as a strategist which was my dream job. But it felt a little bit superficial in how they presented the millenials. It was back then, they do a way better job now but I missed the politics and I felt more comfortable between these fields so I decided to make my own platform Get Me. Through out, (A)WAKE emerged which is now the main katalysator for the movement and cultural program in our shared space MONO.

-So you have (A)WAKE, Get Me and MONO. Can you tell us how all of these initiatives are interlinked with one another and the reasons behind the establishment?

Shirin: Get Me started as an online platform but our offline events became more popular. This whole movement of creatives surrounding us became big and it came to a point where we took over MONO as a physical space for Get Me. But then we had to form a foundation as well to do experiments so (A)WAKE was formed. Get Me is the agency and more Business 2 Business while MONO is where everything comes together. AWAKE is more for the consumer and experiments. With MONO, I got a physical space so it was a scary thing to do because with a physical space you can’t be that fluid and it always needs attention. But on the contrary, it gives opportunities to showcase work from collectives and be sustainable for the people around it. Especially with Get Me, AWAKE and MONO if we find an artist through festivals like New Radicalism, we can also distribute their work to Get Me and AWAKE so this business model is nice. It is the same business model that Dazed and iD, Vice have as well. As one part is focusing on content while the other side focuses on selling that knowledge and talent towards businesses. So combining these elements is perfect. It did a lot for us but it’s also about finding the right balance.

-You have an iraqi-kurdish background. Growing up in Rotterdam how did your background influence the way you thought and perceived the world?

Shirin: That sense of in-betweenness but also working between intellectual and working class domain. It taught me a lot. It means a lot. For me I associate Muslims with humbleness, warmth and being super social so I have very different associations with it. After 9-11 and all of the backlash that Muslims received because of this, I did feel the need to create different sounds and a different platform for them. I do believe that my background motivates me a lot. Also I am aware of the privilege that I have. So being able to switch between these identities, I can easily be more of this Dutch girl within certain context and talk to policy makers and get funding for projects. I would like to use that position for good. Young women would come up to me and say they are inspired that a woman runs this initiative. I never really was conscious about that but I am becoming more aware of this as well and trying to use it more. Because sometimes it is a bit hard to be taken seriously in a room with only men in certain contexts. So it is important to use those privileges and the space.

Photo by Khalid Amakran Vers Beton

-Rotterdam is famous for its underground music scene. Compared to Amsterdam I have heard the arts and culture scene is less commercial and more experimental. In your opinion, why do you think this city attracts avant garde artists and people from different subcultures?

Shirin: I think it’s because there is space here. Cheap places in the city to rent and especially when you look at somewhere like London, it is hard to experiment because it is too expensive. You need a foul proof successful plan because there is no space for failure so I think that makes Rotterdam more attractive. But also the difficult thing about Rotterdam is that there are a lot of people who don’t have access to financial means, especially the youth. I find that quite an issue because how will they be entrepreneurial if you don’t have the means to do so? I wish to see the city invest in Rotterdam based initiatives first before it invests in people from the outside. Now, there are talent scout nights that focus on people who don’t have this formal art education and I think that this is really important because they are feeding them quite a lot of financial means. People are more about movements and initiatives than money and means these days. Which I think I like.

text Ayana Waki

MONO ROTTERDAM

Vijverhofstraat 15 3032 SB, Rotterdam

www.a-wake.world

https://www.instagram.com/mono_rotterdam/

.nl Issue: ひとつのカテゴリやコミュニティにおさまらない人々が集まり、飲み、踊り、生活をするるつぼMONOアートディクターShirin Mirachor/Interview with Shirin Mirachor, artistic director of MONO

1 2