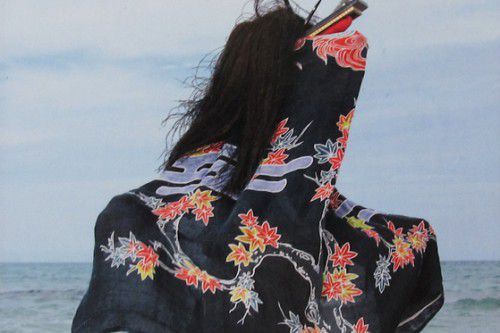

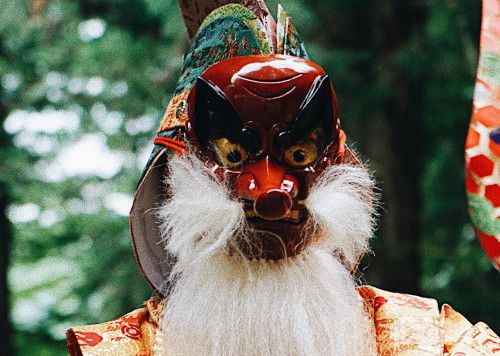

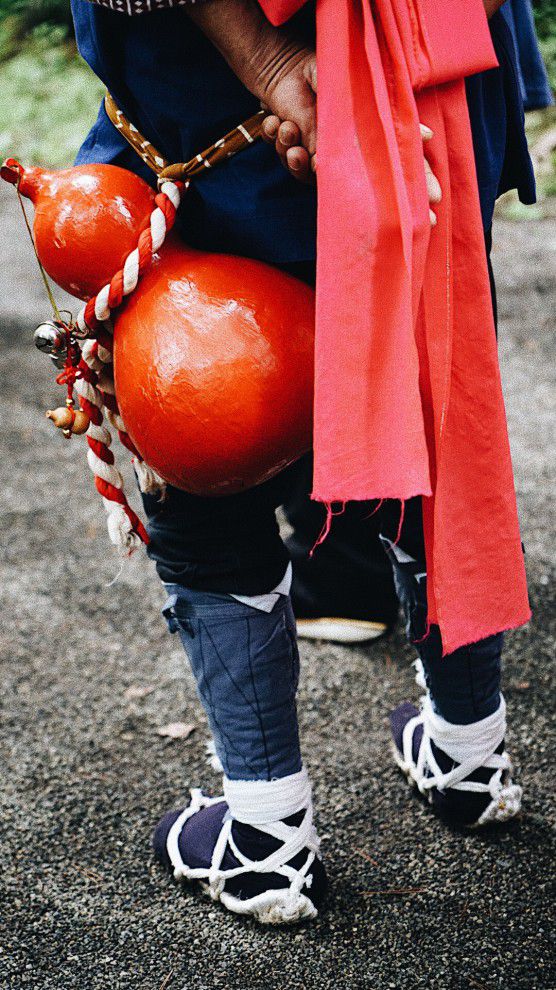

ハレの日の高揚と鮮やかな色彩、力強く厳かな音色――幼い頃から慣れ親しんだ存在であり、私たちの記憶を楽しく彩る“祭り”。祭りは形態こそ異なれど各国に存在し、自ずとそこに暮らす人々の連綿と続く暮らしや風土を反映したものとなっている。その土地の人々のルーツを凝縮させた祭りは、グローバル化が進む中でも民族の多様性を目にする貴重な機会とも言える。

日本には各地に沢山の祭りがあり、それぞれが季節ごとに個性を持っている。“お祭り好き”の民族と自他ともに認めるほどだ。「日本人とは何か」を終生追い求めた民俗学者・柳田国男にとっても大きな関心ごとであり、『日本の祭り』という著書で見解を述べている。

柳田によると、仏教の伝来以前より日本人が古くから信仰してきた神道が、経典を持たないために、神職者は言葉による教えではなくもっぱら日々の行動と感覚をもって伝道する必要があった。そして平日(すなわち特別ではない日)の伝道ははばかられていたため、人々は地域の御社の祭りに参加して神道を体験していたのである。このため祭りに行かない、ということは人々にとっては神道を体験出来ない、すなわち非常にもったいないこととして考えられていた。一般の日本人にとっては、祭りに足を運ぶより他に神の道を究めることは不可能だったのである。そして、四季の循環はその体験を人の記憶に刻ませるための非常に効果的な支柱として作用した。神道の感覚的な教えが、四季の循環そのものに適していたという点が季節ごとの祭りが存在する理由になっていった。

The vibrant colors from the special occasion of Hare’s day, and the powerful sound of a harsh stone striking. These are what I recall from the childhood festivals’ memories. Festivals appear in different form and shape in various cultures and countries. It connects and reflects the people in their natural habitat. It gives us a special perspective to see the condensed cultural value of a country and the ethnic diversity as globalization is taking place.

There are various festivals happening all over Japan all year long, each has a different meaning and stands for different seasons. Japan is recognized as a country that has a profound love for festivals. Kunio Yanagita, a folklorist who spent his whole life focusing on the studies of festivals, had expressed his thoughts and ideas in his book “Festivals in Japan”.

According to Yanagida, the Shinto, which Japanese people have long believed since Buddhism raised its perception, had no scriptures. Consequently, the priests needed to evangelize themselves exclusively through their behaviors and senses rather than spreading the information verbally. And since the evangelism on weekdays (no ritually special days) was not disseminated, it is considered wasteful for people to not go to festivals and experience Shinto on special occasions. It was impossible for ordinary Japanese to understand God besides going to the festivals. The circulation of the four seasons is remembered effectively through the experience as well. The fact that the sensual teachings of Shinto were along with the cycling of the seasons became the reason for seasonal festivals.

彼によると、日本の祭りには“祭礼”と“祭”という二つの側面がある。前者は見物人のための美しく華やかで、楽しみの多いイベント的なものとしての存在。そして後者は神事(儀式)で神を祀るための存在と定義付けしている。

日本の祭りで行われるパフォーマンスはもともと”わざおぎ”と呼ばれ、神の心を和ませ楽しませるものとして発生したというのが通説だ。”わざ”は技、つまり諸業や行動、技術で”おぎ”は(神を)招くという意味をそれぞれ持つ。しかし柳田にとってのわざおぎはそれだけではなく、先述の神道の経験の尊さが人々の身体を動かしたのではないかと考えた。そしてその動きはすなわち経験の直接の効果であり、神がいるという状態そのものを体現していたと述べた。つまり現代のように振りが決まった踊り以前の、よりプリミティヴな身体の動きを“わざおぎ”として考察したのである。

世界的に見ても祭(儀式)とはその行事が正しく行われるために立会人を多く必要とし、また順序の間違えがないよう行列を作る必要があることから大きな空間を必要とした。しかし日本では信仰の特殊性以上にこれを発達させたことで、むしろ様々な形態や規模の祭礼(祭、儀式ではないもの)を起こしたのではないかとも述べている。

According to him, the Japanese festivals has two aspects, one exists to ornate the event beautifully for the spectators and the other is defined as an existence for enshrining the god with a priest which is ceremonial.

It is a common belief that the performance at Japanese festivals was originally called “Wazaogi” and it occurred as a way to rejoice and amuse the heart of God. “Waza” means techniques and “Ogi” has the meaning of inviting (God). However, Yajida’s idea was not only that. He also thinks that the preciousness of the Shinto experience mentioned above also has the power to move human bodies. That movement was a direct effect from th Shinto experience and it embodies the state in which God exists. In other words, we consider the movement of the more primitive body before dance was invented as a modern warp.

The ritual festival worldwide we have in mind all require a large space to take place because it needs a large number of witnesses for the event to be done correctly. The matrix is also needed so that no mistake will be made. However, in Japan it is stated that various forms and scales of festivals are held according to its own specific faith.

Above is just one example of Yanagida’s theory on festivals. The idea of how the modern day festivals we are familiar with have embodied and transformed Japanese spirituality with its special climates is perceived.

Yanagida have pointed out that the festival in Japan has already shifted from ritual festivals to ritual ceremonies as what he had written in his book in 1942. 80 years after that, not only the transition is going forward, the significance of the branching of festivals is also advancing. Individuality of each festival is revitalized for the purpose of the development of the area.

以上は柳田の説のほんの一例に過ぎないが、私たちが慣れ親しむ現代の祭りというものがいかに日本固有の精神性・風土性を体現し変貌させていったものかが分かることだろう。

柳田は、本著が書かれた1942年時点ですでに日本の祭りは“祭”から“祭礼”へと移行しているとも指摘している。この本が書かれてから80年が経とうとしている現在は、さらにその移行が進むだけではなく祭礼の個性を町おこしなど地域の活性化に役立てるなど、その意義は枝分かれが進んでいる。

それではこのように、その地の特性を反映する“祭り”を通じて現代の私たちが考えるべきこととは何だろうか。

柳田国男は、今日では民俗学者として知られる人物であるが、その出発点は農商務省の役人であった。しかし、役人として国が決めた画一的な農業方法を人々に啓蒙しようとしても、うまく成果が上げられずに苦労した。多様な地域の事情を考慮しない、画一的な技術提供の無意味さを痛感した彼は、その土地の人間(特に若い世代)が土地の特性を学ぶことで、一つの方法だけではない主体性を持った考察をすることができ、それが発展へと繋ぐのではないかと考え郷土研究の道へ入った。民俗と教育が彼の中で結びついたのである。

『日本の祭り』は、太平洋戦争勃発直前に柳田が東京帝国大学の学生に向けて講義した内容がベースとなっている。

柳田は当時の若い世代が祭りというものについて考える機会というものはほとんどなくなってきており、しかし遠からぬ未来においてこれが国民総がかりで考えていかなければならなくなるだろうと予測した。これは、グローバル化・多様化が進む現在においてこの予測が的中していたことは言わずもがなであろう。

本著の解説を書いた民俗学者・大藤時彦は、「現代の祭りは参加者ではなく見物人の側にいる者が大部分である」と指摘する。季節を彩り人々を楽しませる祭りだが、それだけではなく、なぜこの祭りがこの地に在り、そしてなぜ私たちは参加するのかということを、主体性を持って立ち返る機会が必要なのではないか。

柳田は、こうして教義(教典)というものに関わりのない人々の信仰、つまり常民による“日本の祭り”というものを通して当時の若い世代に日本人の習俗の起源と変貌を教え、“本当に大切にするべきものとは何か”を考えることの重要性を問いかけたのである。

この問いかけは、現代の私たちにも同じように投げかけられている。

As the consequence, the concern of how we should think through contemporary festivals reflecting the characteristics of different areas like this is raised.

Kunio Yanagida is known as an ethnologist today, but his starting point was the official of the ministry of Agriculture and Commerce. However, trying to educate people about the same agricultural method that the government decided as an official did not work well. He was keenly aware of how meaningless it was to provide the same technology without considering the specific circumstances of various regions. He learned the importance of seeing the characteristics of the land and individuality, later he went into the field of regional studies. Folklore and education was the most crucial thing to him.

He was keenly aware of the meaninglessness of providing uniform technology, not considering the circumstances of various regions, that he (especially the young generation) in the land learned the characteristics of the land, so that it is not only one method I thought that sexual consideration could be made, and I thought that it would lead to development and I went into the path of regional study. Folklore and education were connected in him.

“Festivals in Japan” is based on the contents which Yanagida gave lectures for students of Tokyo Imperial University just before the outbreak of the Pacific War.

Yanagida had made the prediction that the opportunities for the young generation at that time to think about festivals were almost gone, but in the future it might come back to the people. It was inevitable because of its dependence on globalization and diversification.

Yanagida have taught the origin and transformation of the Japanese customs to the young generation of those days through the faith of people who are not related to the doctrine(scripture) in “Festivals in Japan”. “I truly cherish the importance of thinking in which people are capable of asking the core meaning of the customs.”

The question is asked in the same way as we live in our present day.

柳田国男

日本民俗学の創始者。国内を旅して民俗・伝承を調査、日本の民俗学の確立に尽力した。『常民』『遠野物語』は代表的な著作。

出典:『日本の祭り』柳田国男著(角川ソフィア文庫/角川学芸出版)

Amazon.co.jp

Text by Shiki Sugawara

Photography by Baihe Sun