Clubs in London can turn into dangerous places. Incidents of sexual assaults, racism and spiking abound and there have been reports of targeted violence against queer people. In January 2022, a bouncer at an East London queer pub assaulted four party-goers, leaving one hospitalised. In the face of homophobic and transphobic behaviour by the venues and security staff, as well as the lack of care within the club space, Safe Only Ltd, a queer community-led security and welfare team, was established in 2022, authorised by Security Industry Authority (SIA). I talked to Yannis Katsoris, the co-founder of Safe Only, to hear about their practice of welfare, labour and infrastructure of care in nightlife, and how they envision the politics of club events.

—Can you tell me a little bit about yourself, your background, and how you came to start Safe Only?

Yannis: I’m Yannis. I run Safe Only with Dani Singer. Two of us started it together out of the need to make a bit of difference. Both of us were partying for years, we’ve both been party animals. I grew up in Greece, so every summer was party-party, then I moved to London because Greece was not very gay, unfortunately. Then I started going out to the nightlife in London. Even though I was having a great time, there were still times when I had been made to feel unwelcome or uncomfortable by either security guards or staff within the venue who didn’t know how to say the right thing or how to help if I was in need.

Dani and I actually met while partying at our friend’s house, which is quite naughty because we met during the lockdown. When lockdown finally finished, we went out to the clubs again and were so excited to go party. But we saw what was wrong with that again all of a sudden, after being away from nightlife for so long. That’s when we started essentially thinking maybe we need to do something about this.

It happened that we worked the door together at a couple of drag shows, and people loved us on the door together. We thought, you know what, let’s do this. So we took our security licence. We went to security school, and from there the welfare started, which we hadn’t thought about to start off with. The need to actually help people that don’t need security, but need some sort of other help, is always there at parties.

Because we were all partying for so long, the people, the promoters, knew us. So they came to us, and we had bookings from the very beginning. People were very supportive and I think the timing was really good for us.

– In London, there are already some initiatives with a focus on preventing sexual assault such as Ask for Angela or Good Night Out campaign. What was the specific motive for you to start Safe Only in addition to these?

Yannis: Safe Only came out of the need to amplify queer voices, because we feel that queer people have helped shape nightlife but that is sort of forgotten and priorities are different. We wanted to bring something back for the queer people and make sure that they are having a good time – when they do go out, it is a good night, even if it’s like, dramas happen. At least someone is there to help you with that. That’s where we came from and now it’s expanded to all sorts.

—You said earlier about the difference between security and welfare. Can you explain it to me?

Yannis: This is the big thing that we had. We started as security because we thought that was the problem. Yes, of course, there are many problematic security guards, but the problem is the actual current laws. When you are a security guard, you have to follow certain rules and laws from the government, otherwise, you may lose your licence. The government has very strict laws on drug abuse and nightlife. It’s also not very great for trans people at the moment. We realised that just by being the security, we can’t actually provide all the help we want.

Welfare is an invented job. It hasn’t been going around for long. It’s not regulated yet. There are no limitations to what you can do. Essentially, a ‘welfare’ is a ‘welfare person’. We don’t like to say ‘welfare officer’ or ‘welfare security’ – it’s just a ‘welfare person’ because it’s a party person. It’s someone that loves partying, is friends with most of the people at parties, and is there to either help you if you need help getting home, if you’re feeling a bit sick and you just need five minutes to relax, or if you just want to have a random chat with someone. A lot of the time, it is for new queer people that have never been out before, and they’re looking for their people. And having that welfare person there to even welcome you in the venue and tell you like, ‘Oh, you know it’s great, I can help you meet some people, or I’m here if you need anything,’ seems to be going down very well.

It’s nightlife. People don’t only drink alcohol. We have to realise that people like to take drugs as well in nightlife settings. When you are security, because you are bound by the law, even if those who have or used drugs are in harmful situations, you can’t necessarily give them the help that you want to give them. If someone is watching you and you don’t take that person’s drugs, you could lose your licence. But when you are welfare, people can tell you exactly what they’ve taken and you don’t have to kick them out of the club. You can just help them. You can just talk to them or hold their hand. It’s simple things like that that really make a difference in the night.

—Can you tell me how the principle of harm reduction (which focuses on reducing the negative consequences associated with drug use as well as on the wellbeing of those who continue to use drugs, rather than the abstinence of drug use per se) is present in your work?

Yannis: This is where it becomes tricky because, with the current law, you’re not allowed to promote drug use. If you are doing harm reduction, you can’t tell people how to take their drugs. For example, if you go and say to someone, ‘you must take a syringe for your G shot to make sure that you know you’re taking the right amount of G, otherwise you’ll have an issue’, that is something that you’re not allowed to say, and the club could then be shut down for licensing issues. So you have to do it in a way, for example, ‘if someone was taking G, they would have to use this to make sure that this doesn’t happen.’ You have to navigate these small things. You can’t have the tools that you need most of the time, so you can’t give people syringes. You can’t tell them what they exactly need to do.

That’s where the trick is. As I said, it’s very important to call them ‘welfare people’ and not ‘welfare officers’, because they’re essentially just a person at the party whom you’re telling what drugs you’re taking, and they’re telling you how to take them. There’s nothing wrong with that. It’s just people in the party just talking with each other. That’s the window that we need and it’s good to have that option. That’s what we usually tell promoters as well. Obviously, if someone takes a bag of drugs out and we’ve seen it, then, of course, that person has to leave, or at least take the drugs into the bin. But people are clever. They don’t want to be kicked out, so they’ll work with you, little chats, and they’ll understand what you’re saying.

—How would you describe the relationship you make with venues and organisers while working at an event?

Yannis: Most of our customers have come to us already knowing who we are. They usually hire a small team of us and we work along with the club’s security and management. If they have a team of five security, maybe they’ll hire two security from our team and a welfare person or two inside the venue, depending on how big the event is. They tell us if they see someone that needs help, and we’ll go to them. Or if they’re not very sure about an issue that another queer person has, they’ll come straight to us, like ‘This person needs this sort of help, but we’re not sure how to provide it.’

It’s all down to being honest. Usually when we go into a club and work with security, because they are men, and most of the time they have big egos, we tend to stroke their egos instead of poke. So when we have a meeting with them, we say, ‘Just so you know, we’re not here to tell you how to do your job. We’re not here to tell your boss what you’re doing wrong. We’re just here to help you. If there’s anything that you do not know the answer to, you can come straight to us, if it’s something that you don’t know about. That’s why we’re here’. That seems to smooth this situation. We just treat everyone nicely. If they’re doing something wrong, we won’t tell them there and then. We’ll be like, maybe we can deal with this, and then we will send an email with some feedback and what they could have done differently. We won’t tell them off right in front of everyone. We don’t think that people learn like that.

—I noticed that you guys are really visible on the dancefloor, wearing high-vis jackets. Is it your deliberate choice to try to be visible within the space?

Yannis: Yes, it’s all about being visible because it’s so dark in the club. It comes down to our logo: what are the 2 colours that people will remember, something that sticks out? We chose green and purple.. Even if they can’t see where they’re going, they can see the pink jacket. So they just come to the jacket. It helps a lot.

—Your website mentions that your staff are paid the real living wage [As of June 2023, the national living wage, the minimum wage for 23 and over, is £10.42. Different from this statutory amount set by the government, the real living wage, a voluntary level of wage for 18 and over that considers the cost of living, is calculated as £10.90 across the UK and £11.95 in London by Living Wage Foundation. Some however say it is still not enough and are calling for £15 minimum wage]. Could you elaborate on the terms of labour and care that you provide?

Yannis: This is a tricky one because we’d like to pay our staff a minimum of £15 per hour, which for London at the moment is quite significant. Usually, a security guard in a nightclub setting will probably get £11 an hour. And that is working 12h shifts in a nightclub with potential damage to your ears, dealing with a lot of vulnerable situations. Essentially, you’re protecting all the people in the venue but you also have to protect the venue from people destroying it. There’s a lot to it and you’re expected to do that just for £11 an hour, which to us is ridiculous. London is very expensive. If you’re just making £11 an hour, maybe just 3 times a week, you are going to need 2 or 3 more jobs to maintain your basic living. For us, if you’re expected to do all that work and keep all these people safe, you need to be paid the right amount of money. Even 15 pounds is not the best, because nighttime work is bad for your health, changing your body clock and everything. But it’s the best that we can afford at the moment and make sure that we keep having bookings because we want to keep the relationships we have with the promoters.

The minimum that we’ll charge promoters or venues is usually £20. The £15 goes to the worker, and £5 stays in the company. And that usually helps with taxi schemes. We have a taxi scheme where people can buy a taxi after their shift, and we can pay up to £20 for it. We buy uniforms and when we have a team meeting we’ll buy snacks and we’ll provide stuff for people from the money that stays in the company.

We want to book more promoters because, currently, we have events every weekend in London where we have a team of people working. It’s very important for us that we stay with these circles and continue this work. Now people say, ‘Oh, I love these pink, high-vis jackets’, ‘Every time I see them in this jacket at a party I feel like I’m safe.’ For us, it is amazing that people recognize who we are and want us at the parties. They go to the promoters and ask them ‘What are you doing to make your party safer? Do you just want our money, or do you want us to be safe at your party?’ It’s changing a bit of the attitude. A year or 2 ago, people would not be willing to pay these wages. We are now seeing parties that are paying them. Parties that maybe didn’t book us last year are now coming back to us, rediscussing these prices.

It shows that if the service is good, needed, and making a difference, people can suddenly find the budget for us. Whereas before, security and welfare was the last thought. People do not budget for it. So they pay the least money that they can, but then they complain about the service they receive. Because it’s all outsourced people. On the other hand, our workers are happy to go to work and give their best selves, because they’re getting paid what they should be paid and feel valued. Eventually, we want to pay our workers more. But for the time being it works.

—What would you say to the idea that care within the club is the responsibility of the organisers, venues, or promoters, rather than something that should be outsourced to other places? Or maybe that, because they outsource the labour to you as a specifically queer welfare team, they don’t fundamentally change what they do. What do you think?

Yannis: That’s something we’re navigating now, because we found that a lot of clubs and venues thought that, just by booking us, that’s enough. So they put our name next to their party like we have Safe Only so you’ll be in safe hands. But sometimes care extends beyond that. It’s not just we have one person at the party, and we’re doing the best we can. It’s everything that goes with it. Do you care about the people that work in your venue, even the bartenders, even the cleaners of the venues? Because most of the time when we go on shift, it’s the actual staff of the venue who come to us and complain about their working conditions.

We’re discussing how we can navigate this. How do we tell promoters that we’re not just a token to show and that you actually have to change the structure of the current system? You have to help us make this change. There’s more to be changed. Eventually, if we make a union, we can all represent ourselves and maybe try and change some laws around drug abuse or all that, but no one seems to care about that.

We’re telling people that people can try and think about how else they can provide for the community rather than just throwing a party. It’s great to throw a party for all the queer people. But we want to ask, do you care about them when they leave the venue?

As a team, the dream is eventually to have enough money to rent our own space and then people can come every Tuesday to just come and chill in the office and maybe watch a film with us, or just chat, for people to have that point after a great weekend. You know it can be very lonely to have the best weekend of your life and to be all by yourself the next day in your flat. And it’s so hard, you need someone to just maybe be in the same room with you. So the dream is, to one day offer that space to all the queer community in London. It would work as a Safe Only office, and people could come and chill with us, sit in our office while we respond to emails and tell us how your day’s going.

—I was wondering whether you have training for the members of your group and how you distribute the skill set. The first time I saw one of you, Alex, I was looking for my friend at a club who I thought went missing. Alex was describing my friend to the security guard at the door in a way that didn’t assume the gender of my friend: just talking about the presentation, like how tall, etc, which was really helpful for me at the time. Not assuming people’s identity might come naturally to queer community, but how do you train your members on other things that require certain skills?

Yannis: The number one thing is that we’d only like to hire queer people. That is a big advantage already. If you are queer, you have most likely interacted with other queer people. You know what the current issues are so that always helps a lot. That obviously is a big bonus for our team. A lot of our welfare people already have medical knowledge. They’re either mental health nurses or nurses, or they’ve been caring for people with autism or elderly people. They have some background knowledge already, and they all are party people.

But we have our induction days. We meet up with new team members and we tell them exactly how we like to work, how we see it going, and what our vision is. And we have chats with them and get to know where they are at, mentally, at their stage. Are they at the same stage that we are at the moment? Or do they need to maybe shadow us a few times in a shift, and then they can provide the same service, that same Safe Only one? So it’s all peer-to-peer conversations, mainly. A lot of them haven’t gone to security school. But if you are just welfare, it is more like peer-to-peer. Because you can still be queer and… For example, if you are gay you are not necessarily affected by a trans person’s issues. You might not necessarily know the current issues they have. That’s something one learns from the actual experience as well or from being told. Shadowing is very important on shift, because we get to see how they interact with customers, and we see what level of knowledge they are at and what care they can provide.

Then we distribute them to the party. Some people have selective parties that they only want to work at because they know that community and that’s where they feel comfortable to provide the best care they can.

—Some of the Instagram posts from Safe Only said you want to make space for people who are neurodivergent, making sure that they can also come to the party. What specific challenges do they have?

Yannis: A lot of the time, when you think of a club, all they care about is how to have the best sound system or how to look cool. Because of that, people with accessibility needs and those who are more sensitive to loud noises or set different lighting are overlooked. It’s because, unfortunately, the majority of people do not have access issues or do not have these sensitivities. But they still want to go out and still want to have a good time.

We try to have conversations with the promoters and the club owners and ask them what they do about these people. Because these people still come to your club and pay you money. How do you make it better for them? So we always make sure to have a little space so that people can sit without music even for 5 min, just to calm themselves. We try to make sure that there are access points for people with wheelchairs or on crutches, so they can still come to the club. Because some venues don’t even have this. I mean, not even the London Underground is accessible to people with wheelchairs.

It’s so easy to overlook and forget these people. But they are part of our community. We have to constantly remind ourselves: what are you doing for people that are sensitive to the sound, but still want to come out and have clubs? Do you have earplugs in your club? It’s just reminding people all the time what they need to have in their clubs to make it safer.

—How would you describe your team members right now? How big is the team? What are their backgrounds like?

Yannis: We have a welfare team of maybe 20 people, a security team of 10 people, and we also have 4 medics, medical assistants. They are proper doctors, gay doctors that go to clubs and help (laughs). We have a very diverse group and we have a lot of POC people in our team. We have South Asian. We have different European countries and obviously people from England. But our queer community is diverse by itself. Everyone comes to London because they’ve left their hometown to find the queer scene.

We make sure to hire people from as many different countries as possible. There are so many people in London, for example, Nigeria, and these people are also queer. We have team members that are from around or maybe from another different country in Africa who relate to the issues and maybe can tell us if we’re doing it wrong. I think we need to listen and we are open to that. We want our team members to tell us if we get it wrong because Dani and I are both White and European. We’re not playing god and know that we’re going to make mistakes.

But their backgrounds, they’re all queer. They all came to us, either through Instagram or seeing us at a party, and asked us how they can work with us. It’s really exciting. We do have a soft spot for our trans community. So we try to have as many trans people as possible in our team. We have our Clapham gays, East London queers, and trans dolls. Everyone is part of the team.

—Can you explain a little about the problems that trans people face?

Yannis: It’s terrible how trans people are discriminated against right now in England. It happens on a daily basis and seems to be getting worse and worse every day. The only thing that we can do is make sure that these trans people are as safe as possible. So it’s by giving them a job. This is why we find it superb that we created a team of mainly trans people because they all came to us because of issues they’ve had at their previous jobs, being discriminated against for being trans or not being able to be themselves a hundred per cent. And they’ve all come to us because they feel comfortable and can feel that they can be themselves. They can tell us their problems, and we will listen and try and help them. Dani, my business partner, is also in the trans umbrella. My housemates are all trans. It’s a community that’s very close to our heart. So we try our best to do as much as possible for it.

—A lot of queer people, especially trans people, when going through the security at the door through the bouncers and having to show their IDs, must have a lot of really negative experiences. Do they find it easier that there are queer security members? Or they just don’t want to trust security at all?

Yannis: We don’t question. We’ll look at the name that’s different. We’ll look at the photo that’s different. But we know that this person is trans and is not faking the ID to come in. You won’t question that. It’s not even asking them ‘Is this you in the photo?’. Well, yes, it is me, but it is me 10 years ago when I was presenting differently. We don’t want to bring that person to that stage. We don’t want to ask them that question. We’ll acknowledge the fact. We’ll give them a smile and say, have a lovely time inside. That already makes that person feel so much better. Even before they enter the club they feel at ease: ‘Okay, I can relax. These people get it. I’m fine. I can have a good time here.’ It’s such a small thing that makes such a big difference for some people.

—What do you want to achieve in the near future as a team?

Yannis: All the long-term goals that we sort of had, we’ve almost achieved. All the parties that we wanted to be present at, we finally have a presence there with security and welfare. A closer dream would be to maybe have a bigger security team, because we’re finding it hard to have only queer people as security. So one of our immediate dreams would be to get some funding and be able to pay for the licence because it’s very expensive. You have to pay £500 for their class, and £250 for the licence. For a queer person that usually can be a lot of money. Not a lot of queer people have got money. We would ideally be able to pay that for a big team, maybe send 10 or 20 people to security school for a week and then have them on our team. Once we have a much bigger team, we can actually start taking over clubs completely rather than working with their security. We could just have our security and that would make such a difference.

Most of the issues that we have when we work with other security are to make better after their mistake. So hopefully one day we’ll be able to just take over a whole club, and just for my team. It’s a dream, but it’s happening. It’s getting there.

—Lastly, what is club space to you? What kind of club space do you hope to create and go to?

Yannis: To me, it’s total freedom. I have been a partygoer for years, and I now tend not to party at places anymore. They don’t give me the total freedom that I want to feel. I’m longing for a place just like utopia – a place where people acknowledge each other, and there is an acknowledgement that people are in different situations, where harm reduction is at its core, making it safe for all drug users and for all the people that want to have that sex in the dark room.

*One example in Tokyo where harm reduction was discussed in the club context is the open discussion hosted by the club event ‘ether’ in 2021. ‘WAIFU’, the first club event in Tokyo to introduce the safety team as a community project, lets clubbers as well as the organisers wear a SECURITY sticker at the event if they want to help make the space safe so that people can approach them if something happens.

Text Yoshiyuki Ishikawa(https://www.instagram.com/yoshiyukiiishikawa/)

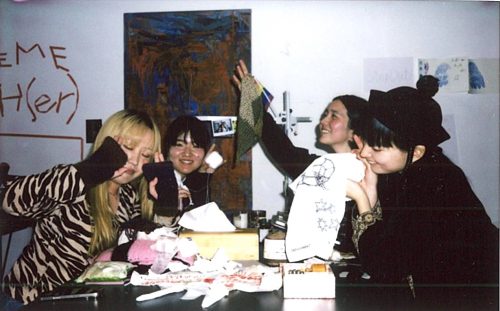

Photos Safe Only Ltd

Safe Only Ltd

Home https://www.safeonly.co.uk/

Instagram https://www.instagram.com/safeonlyltd/